“Gendered” spaces exclude and hurt a lot of people; we can — and should — design better.

Photo by Tim Mossholder on Unsplash

There are many ways that public spaces hurt and exclude people. Binary gender restrooms are just one example that I can speak to based on both personal experience and professional expertise. There are many others, and they all deserve attention, so I welcome other voices to contribute to this space.

Restrooms are a very unique type of space — they are the one place where we all do the one thing that we all do.

In an odd way, they sort of unite us. Restrooms can be a great equalizer (everyone needs them), but they also perpetuate a lot of inequity.

This happens to me all the time

Let me tell you a story to help frame some of these issues. A few weeks ago, while my flight was delayed in Minneapolis, I needed to use the restroom. This seems like a pretty normal, mundane task, but for people like me (and many others, for many different reasons), it can be an incredibly stressful situation that is loaded with trauma.

To paint a better picture for you, I am six feet, two inches tall, and present in a way that many people would describe as androgynous. I don’t necessarily disagree with that characterization — in fact, I’m proud of the work I’ve done in therapy to finally be happy with myself. I identify as female and use she/her pronouns. I also use the “women’s” restroom when presented with binary options.

After I exited the stall, I went to the row of sinks to wash my hands. As I was washing my hands, an airline employee walked in, looked right at me, and loudly said, “am I in the right restroom?” This question was clearly directed at me. And I was so embarrassed because there were other people in the restroom, all looking at me for the answer.

Suddenly, I felt really, really small and unsafe.

But I was forced to answer, “yes, I’m a woman,” because everyone was looking at me for the answer to her very public question. I can’t tell you how embarrassing this type of situation is.

But when she saw the look of embarrassment on my face, instead of acknowledging her harassment (because that’s what it was) — she said, “oh, I saw your short hair.” This just made things worse. My hair is not my gender, and instead of apologizing, which is what she should have done, her comment was really an attempt to excuse her hurtful words.

I had been traveling all day, my flight had been delayed multiple times, I was traveling with my rescue dog during a global pandemic with a raging variant. I was stressed out and just wanted to get home to visit my family. But suddenly I was forced to defend myself and my identity in front of a bunch of strangers, in a really vulnerable place?

What’s even more confusing when this happens is that her question is really about her, not me. I have no idea if she’s in the “right” restroom. Why is she asking me?

And this is by no means a unique situation. This happens to me all the time — to the point that I, and other members of my community, have developed a variety of strategies to manage or avoid it, including:

Waiting to use the restroom until it is empty (and then hoping no one comes in).

Literally running out of the restroom as fast as I can.

Awkwardly waiting in the stall until everyone leaves, which generally results in me being late for a meeting or a class.

Talking in as high pitched a voice as I can even if it’s only to myself.

For the last strategy, I often use the “buddy system” and only use the restroom with a friend or partner who I can have a conversation with, so people hear my voice. It’s really awkward.

This happens to me so often that I can tell you every restroom in downtown Seattle (where I live), where I feel safe; and I lost track of the number of meetings or classes I’ve missed because I had to employ one of these strategies or go far out of my way to use a safe restroom.

Does this all seem ridiculous? That’s because it is.

Yet every time I share a story like this, so many people reach out and say they can’t believe this happens. If you take one thing away from this article, I hope it is a greater understanding that this type of harassment (and many others) happens all the time.

The second key take-away is that this situation — which originates from an extremely outdated and exclusionary design strategy — is not just embarrassing, it has direct and negative health impacts to certain users.

Put another way, poor building design can be directly tied to negative health outcomes. Let me explain some of the research.

Building design impacts human health.

My work focuses on creating sustainable, healthy and inclusive spaces. So I spend a lot of time researching how spaces, and specifically buildings, impact human health and wellness.

While there are many ways that restrooms, and particularly gendered (i.e. “men’s” and “women’s”) restrooms exclude and hurt various groups, in this article I am going to focus on the trans community.

The research clearly links gendered restroom design to negative health outcomes.

The 2015 US Transgender Survey, the largest ever survey to record the experiences of transgender people in the United States yields some heartbreaking statistics:

“More than half (59%) of respondents avoided using a public restroom in the past year because they were afraid of confrontations or other problems they might experience.”

“Nearly one-third (32%) of respondents limited the amount that they ate and drank to avoid using the restroom in the past year.”

“Eight percent (8%) reported having a urinary tract infection, kidney infection, or another kidney-related problem in the past year as a result of avoiding restrooms.”

Read that again: nearly a third of the trans community limits their intake of food and water to avoid the harassment, intimidation, and worse, that occurs when forced to use a “gendered” space.

This research is critical for advocates because it directly connects poor restroom design to negative health impacts.

We can do better — we just choose not to, and that says a lot about us.

Every time I share these stories and statistics, folks ask what they can do. I see at least two things you can do:

First, raise awareness that this happens all the time. Every time I consult with companies looking to pursue more inclusive design, they are shocked by these stories and statistics. And I need to be clear that restrooms are just one way that buildings exclude certain groups and welcome others; unfortunately there are many other examples and many other groups who are hurt by poor and discriminatory building design.

Be on the lookout. Be a safe space. Speak up when you see and hear harassment.

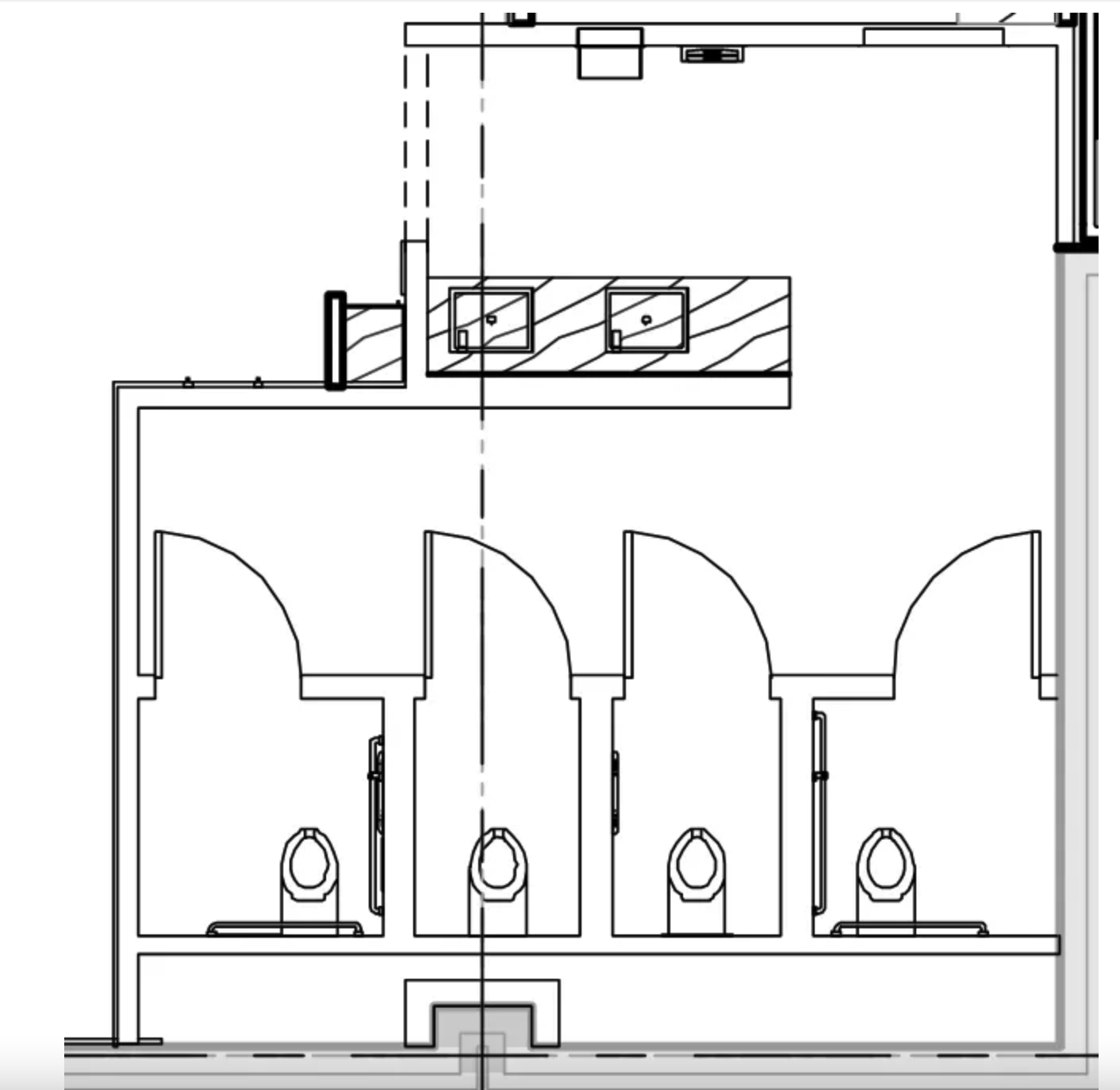

Design detail from an inclusive restroom at PCC Community Markets

Second, elevate examples of inclusive, health-forward design. There are two excellent examples of welcoming restroom design in Seattle that I would like to share: PCC Community Markets and Town Hall Seattle.

The design detail on the right shows an inclusive, non-gendered restroom at PCC Community Markets, a co-op grocer in the greater Seattle area. It has single stalls, common sinks and does not force users to choose from a binary gender designation. One bathroom, for everyone.

The image below is from Town Hall Seattle, a cultural center and performance hall. This design also consists of one main entrance which flows into a series of single stalls with floor to ceiling doors, and ends in a row of sinks. The only sign on the door is “restroom,” and traffic easily flows through the space and out the common exit.

Image courtesy of Town Hall Seattle.

Another key feature of these examples is that the inclusive design benefits all users, and it does not force users to disclose confidential information in order to get the support they need from these spaces.

Put another way, a user should not have to disclose, for example, that they are transgender in order to use the restroom. This often happens when a person who may present as male chooses to use a single-stall, non-gendered restroom over a “men’s” room. Other building occupants may make assumptions about them based on their choice. Good design does not force users to disclose private information.

These examples demonstrate that case studies exist, which really begs the question, “what is our excuse for not doing better?”

Design change versus behavior change.

Circling back to my story about Minneapolis, I am well aware that while part of the issue is the design of the space, the other part is training for the benefit of the airline employee who used those hurtful words. But, if the space had a more inclusive design, there would be no question as to whether I, or anyone else, was in the “right” restroom, because there is only one restroom. One restroom, for everyone.

UPDATE: the 2022 US Trans Survey Early Insights report was just released.

The report has updated information and data on the health impacts of poor design. Read the full report by clicking the button below.