Unfortunately, most office spaces are not designed for a diverse range of users - and that needs to change.

Advocating for the office space you need to do your best work is a form of radical self-advocacy. It’s also an active rejection of hustle culture. Let us be clear: you do not have to “suffer” with a workspace that does not meet your needs in order to be a “good” employee or climb the corporate ranks. In fact, the research is clear that you will perform better if your workspace works for you. We teach our clients how to advocate for, and build, great spaces that set everyone up for success!

It is an outdated narrative that you have to suffer with an uncomfortable workspace that doesn’t work for you. Reject this toxic, biased narrative and advocate for the ability to do your best work. You don’t have to be set up to fail; you can set yourself up for success.

Photo by Petr Magera on Unsplash

Here’s the reality: most office spaces are designed for straight, white, neurotypical, cis-gender men over about 50 - 55 years of age. These are the folks who do really well in "traditional" office spaces.

If this isn't you, you are, at best, not getting a fair chance to shine your light bright and share your talents with the world; and at worst, you are being set up to fail - and you deserve better. We have the research to back this up and the strategies to create spaces that work for a more diverse range of users. And these strategies can range in cost and impact - which means there are lots of options available - and they can also be adapted to a work from home or hybrid environment. There really just isn’t an excuse.

Taking control of, and advocating for, a workspace that works for you is an act of courageous rebellion against multiple structures designed to hold you back.

If you’re an employee struggling in a space that doesn’t work for you, we can teach you how to advocate for yourself. And if you are an employer, and you actually care about your employees, we can show you how to demonstrate that care through better office design.

Let’s break down each of these aspects, before explaining how to do better:

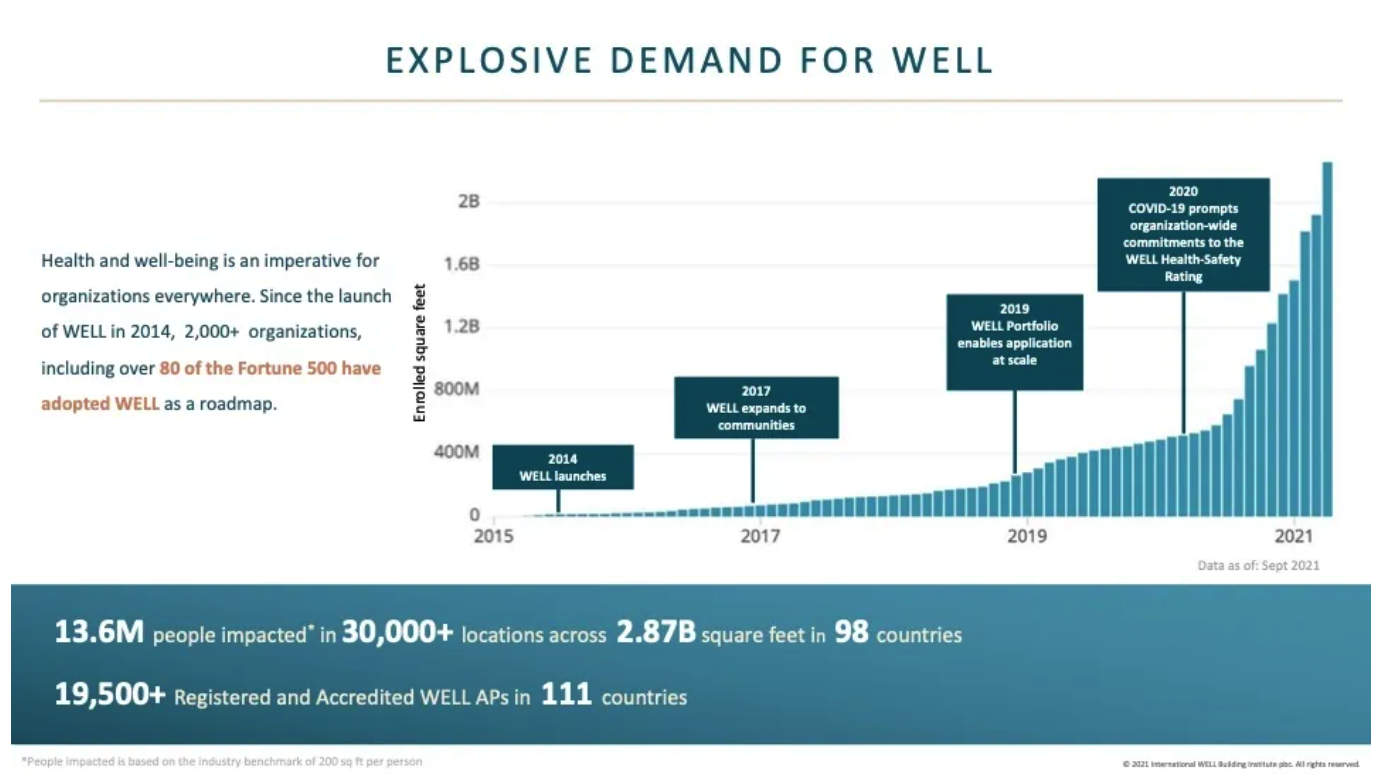

We are now an indoor species. On average, North Americans spend 90% of their time indoors and 1/3 to 2/3 of their waking hours in office spaces. These are pre-pandemic data points, so you likely spend more than 90% indoors, and while you’ve likely spent less time in office spaces over the past two-three years, this is why the Return to Office conversation must include considerations related to the inequities that are often associated with physical office spaces.

Again, most office spaces just don’t work for many users. Let’s walk through a few specific examples:

Temperature considerations or thermal comfort:

Have you ever been really cold at work; so cold that you’re uncomfortable, distracted and grumpy? There’s a reason for that:

There’s actually a very narrow range of temperature that supports optimal human performance. Thermal comfort “standards,” which govern facility operations in most commercial spaces, are based on the clothing choices and metabolic rates of cis-gender men in the 1960s. Yet the metabolic rate of women can be up to 32% lower.

This impacts your ability to work. As noted by the authors of Healthy Buildings:

“Researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory found a 10 percent relative reduction in performance when the temperature fell out of this narrow optimal range.” [1]

This is one reason why “traditional” office spaces work really well for cis-gender men, but many others struggle in these spaces. Temperature differences disproportionately impact the performance of certain building users — particularly women. Work doesn’t have to be uncomfortable; you don’t have to be “tough” about your workspace - and as the research shows, you will perform better when you don’t have to - by about 10%.

And based on our experience, if you raised a concern about the temperature of your office, you were likely dismissed as “whiney” or “complainey,” if you were even able to get a response. Or if you raised a concern in the past and it wasn’t handled well or taken seriously, who can blame you for not trying again?

You have the right to be able to do your best work and that includes the right to a workspace where you are comfortable and can focus. And there are many ways (ranging in cost and complexity), to support diverse thermal comfort, including: flexible dress codes, thermal “zones” with different temperatures, and the ability to choose where you work best (and trust from your employer to do so).

Creating safer spaces

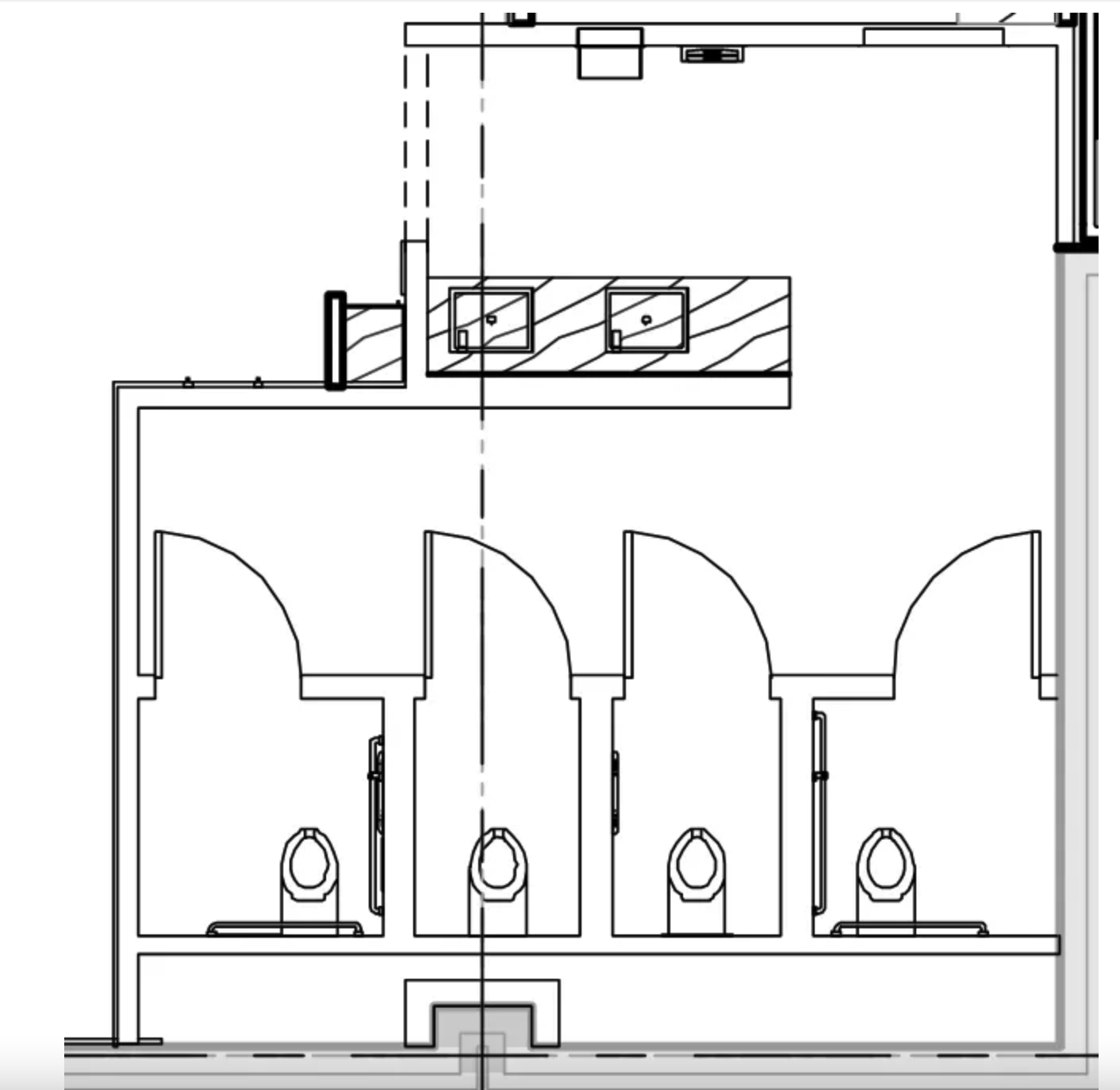

Office spaces have restrooms; they are the one room that we all need, because we all have to go to the bathroom. They are sort of a great equalizer, yet the impact of these rooms is highly disproprtionate.

Poorly designed spaces - including “gendered” restrooms (i.e. a “mens’” and a “women’s” room) - hurt and exclude many users. The research clearly links “gendered” restroom design to negative health outcomes. For example, the 2015 US Transgender Survey, the largest ever survey to record the experiences of transgender people in the United States yields some heartbreaking statistics. And if you have been paying attention to the news, attacks on the trans community have steadily increased since 2015, so we expect the updated results from the 2022 survey to provide even greater support for the argument that more inclusive restrooms are desperately needed. [2]

Example of an inclusive restroom with individual stalls and a common sink area. Photo courtesy Town Hall Seattle

The 2015 data demonstrates:

“More than half (59%) of respondents avoided using a public restroom in the past year because they were afraid of confrontations or other problems they might experience.”

“Nearly one-third (32%) of respondents limited the amount that they ate and drank to avoid using the restroom in the past year.”

“Eight percent (8%) reported having a urinary tract infection, kidney infection, or another kidney-related problem in the past year as a result of avoiding restrooms.”

There are lower cost, lower impact strategies and higher cost, higher impact strategies (and everything in between), to be considered, and restroom redesign always requires associated training and education to help ensure safe and respectful experiences for everyone. These strategies can range from a complete redesign of a single restroom for all users (image to the right), to simply revising the signage (example below) to indicate what type of plumbing is in a certain space and inviting users to select which room meets their needs.

Signage Example: https://blog.bidadance.org/2018/07/gender-inclusive-restrooms.html (Boston Intergenerational Dance Advocates)

Support for a Neurodiverse Workforce

Most office spaces are designed for neurotypical folks; but neurdiverse folks are is a significant percentage of the workforce:

“Seventy million people in the United States have learning and thinking differences, such as dyslexia and ADHD, according to Understood.org. That’s roughly one in five people…. The current workplace is not set up for the neurodiverse to succeed, and they often encounter bias from others who dismiss them because they don’t follow the norm. This is a huge opportunity for companies, because when the neurodiverse are aligned with jobs they are most qualified for–they outperform their peers.” [3]

Designing a Neurodiverse Workplace, HOK, https://www.hok.com/ideas/publications/hok-designing-a-neurodiverse-workplace/

By failing to create office spaces that support neurodiverse workers, we are depriving folks of the ability to do their best work and missing out on all the creative and innovative ideas that could be brought to the table.

Design plays a big part in this conversation, and there are numerous design strategies that can be used to create more inclusive spaces, including those outlined in the box to the right. Among many other reasons, this is why we need professionals with diverse lived experience designing the spaces where we spend so much time.

The disproportionate impacts of a forced return to the office are elevated when neurodiverse folks - many of whom have created work from home spaces that work for them - are forced into traditional office spaces without proper support.

Everyone deserves the chance to do their best work, and we can do so much better.

Employers need to do better.

There are many other examples of the disproportionate impact on health and wellness of traditional office spaces. These impacts are particularly important in the context of the Return to Office conversation, because health and wellness are key values that employees are looking for. According to recent research by Deloitte, “Sixty percent of employees, 64% of managers, and 75% of the C-suite are seriously considering quitting for a job that would better support their well-being.” There’s also a significant disconnect between what employees are experiencing and how leadership is perceiving their experience, “Most employees say their health worsened or stayed the same last year, but more than 3 out of 4 executives believe their workforce’s health improved.” [4]

Employers are clearly not asking their employees how they are doing, or they aren’t listening.

Suffering in work environments that don’t work for you is a part of toxic burnout culture and a variety of other structures designed to hold certain groups back. You have a right to the opportunity to do your best work. And in some instances, such as licensed professions with fiduciary or standard of care obligations, there’s an increasing argument that these spaces are a necessary part of meeting those obligations - you need to think clearly and do your best work to meet those standards.

Everyone - everyone - deserves the chance to do their best work; and as we’ve shown above, the research demonstrates that traditional office spaces set many folks up to fail. If you’re a corporate leader and not providing diverse employees with safe spaces where they can succeed, you are not living your diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging values; and if you’re forcing employees back to “traditional” spaces in light of all the research that demonstrates the disproportionate impacts, you are potentially creating some serious liability issues.

Here at Sustainable Strategies, we are fearless champions for sustainable, inclusive spaces that support health and wellness. If you need support, reach out and we would be happy to schedule a call.

Notes and Resources:

[1] Allen and Macomber, Healthy Buildings: how indoor spaces drive performance and productivity, Harvard University Press (2020); https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/is-your-thermostat-sexist; find original Lawrence Berkeley research

[2] https://www.ustranssurvey.org/reports This resource from the ACLU and this resource from UCLA’s School of Law. We will provide updated survey data on this website, as soon as it is available.

[3] Forbes: Neurodiversity: Supporting the invisible disability in the workplace, https://www.forbes.com/sites/shelleyzalis/2023/07/25/neurodiversity-supporting-the-invisible-disability-in-the-workplace

[4] https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/topics/talent/workplace-well-being-research.html. For more information on the impacts of poor air quality and spaces that lack natural elements, see this blog post https://www.sustainablestrategiespllc.com/on-our-minds/how-healthier-buildings-add-value.